- Staff

- #1

- Joined

- Oct 21, 2006

- Messages

- 48,046

- Reaction score

- 32,156

- Location

- Edmonton/Sherwood Park

- Website

- www.bumpertobumper.ca

Study Calculates EVs Have Higher 'Real World Refueling Cost' Than Gas Vehicles

But read the fine print, as the study makes some assumptions and some scary claims about electric cars.BY SEBASTIAN BLANCO

OCT 25, 2021

EXTREME MEDIAGETTY IMAGES

- If you've been paying attention to the development of electric vehicles long enough, you know that there are endless factors when calculating just how clean or dirty or cheap or expensive they are.

- To give buyers an estimate, the Anderson Economic Group has put out a paper trying to figure out the real-world cost, in time and money, of making the switch from gas to electric.

- We took a closer look at their conclusions and the methods they used to arrive at them.

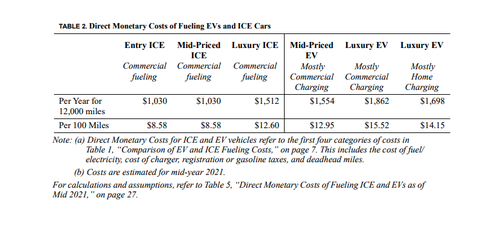

For example, based on gas prices in Michigan, where AEG is based, the study says the "direct monetary cost to drive 100 miles in an internal-combustion (ICE) vehicle is between $8 and $12, and in an EV is between $12 and $15." That sounds alarming, and the results show that in all of their three scenarios, it costs more to refuel using electricity than gasoline.

But take a closer look at Table 2, and you'll see that three types of gas-powered cars are listed: entry, mid-priced, and luxury. For the EVs, there are also three columns, but they include one mid-priced and two luxury EVs (one that's "mostly" charged at home, and one that's more often charged at a public charger).

ANDERSON ECONOMIC GROUP

More important is noting that t

More important is noting that the study assumes odd habits for an EV driver who "mostly" recharges at home. How odd? The study assumes that it takes a whopping 5 minutes to plug and unplug an EV using an installed home charger. This feels way too long, but if we accept their time and use their assumption of 25 charges a month, we can see how they calculate that charging at home eats up 2.1 hours of time a month. But the paper doesn't use that time figure for the home charging example. Instead, it also assumes people with home chargers actually conduct 40 percent of their charges at a public, commercial station. This, then, allows the study to claim that they spend 4.5 hours a month charging their car.

At-Home vs. Away-from-Home Charging

Being able to charge at home is key to the ownership-cost equation, and we would expect that the charging ratio of many EV owners is more like 90/10 percent in favor of at-home charging. Over the past two years, our long-term Tesla Model 3 is running at a 55/45 percent split in favor of at-home charging, and we would expect our figures to be on the high side of commercial charging as ours is constantly driven by people without a 240-volt hookup at home and also going on long trips.Here's another example of the study's methodology. The paper makes the case that charging an EV takes longer than an internal-combustion-engine vehicle. This is true for anyone who can't charge at home—and it is undeniably a real issue—but then, in order to estimate the cost of the extra time it takes an EV driver, the authors assume two rates: a $9.65/hour minimum wage as well as an annual salary of $70,000. According to the Social Security Administration, though, the national average wage index for 2020 was just over $55,000. ZipRecruiter says the average annual pay for a national in the United States is just over $74,000 a year, but also says that the "average pay range . . . varies greatly (by as much as $52,500)."

In any case, by using the higher estimated wage, the study authors are able to show that EVs "cost" a scary amount in lost time because they assume that each minute of time it takes to charge is worth more money than if they had used a lower annual salary.

Then let's look at how the study authors deal with "free" public chargers. They admit that these options exist, but then say that they "recognize that ['free' chargers] involve a cost that must be paid, and which may be embedded in property taxes, tuition, consumer prices, or investor burdens." Their solution? They simply "price [the free chargers] using commercial rates." Well, isn't that convenient? And you can probably guess how they deal with the various free charging bundles that some automakers offer with the purchase of a new EV. That's right. Instead of counting it as zero cost, they price it like other commercial rates.

Consumption vs. Efficiency

There's more. While the paper mentions that "EV buyers typically receive a Level 1 charger along with their auto purchase," they still include a $600 fee to buy one in their tally of costs. They also make another gaffe when calculating how much energy is needed for each vehicle. Although they cite our piece on charging losses, they apparently forgot to read the one on consumption versus efficiency, because they use EPA combined efficiency figures in their calculations—those already include charging losses—and then add another factor of 88 percent to account for charging losses. Unwinding the double counting lowers the cost figures by more than a dollar a piece to between $11.72 and $12.97. And if you instead assume home charging in a 90/10-percent split, the cost of the luxury EV drops to $10.50 per 100 miles, handily beating the luxury gas-powered example. As we have also pointed out, the percentage of commercial charging makes all the difference, as our Model 3 is no cheaper to fuel than our long-term BMW M340i when always charging at the far more expensive public chargers.The authors admit that what they've created here is not exactly a scientific study, noting that they include data from EV drivers "posted on forums for Taycan and Tesla drivers; Reddit; and applications serving EV drivers such as PlugShare and ChargePoint." In other words, all of the squeaky wheels who went to post a complaint got the grease here, while all of the people who had uneventful charging sessions—and thus didn't post—were ignored.

Perhaps most convenient, though, is how the Anderson Economic Group's paper ignores any mention of emissions or climate change. Say what you want about this figure being difficult to calculate, but it feels disingenuous not to at least address the topic.

And it's not like no one has tried to calculate the different emissions between ICE vehicles and EVs. Polestar's recent life-cycle analysis comes to mind.

To be fair, completely seamless EV charging remains a pipe dream for most people. Changing the world's transportation infrastructure is taking a long time, and it's messy. The examples that the paper cites about broken or otherwise non-working charging stations are a real thing. The paper can make a good case that for people who aren't able to charge at home, EVs present hassles that gas vehicles don't. The "deadhead miles" when you have to go out of your way to find a charging station can be a pain—and should be kept in mind.